GxP Lifeline

Turning Mistakes Into Marvels on the Manufacturing Floor

Errors. Oversights. Accidents. Mishaps. Bloopers. Gaffes. Fails. Call them what you will, mistakes are unavoidable. And while they usually carry a negative connotation, sometimes a mistake can make a lasting impact for the better.

Many inventions are said to have happened by mistake, perhaps none more famously than penicillin. In September 1928, Dr. Alexander Fleming, a bacteriologist at St. Mary’s Hospital in London, returned from vacation to find that a mold had contaminated his Petri dishes housing some colonies of Staphylococcus aureus, the type of bacteria responsible for most infections. While examining the dishes under a microscope, Fleming discovered that the Penicillium mold prevented the normal growth of the staphylococci. And so penicillin was born.

As the adage goes, you can’t control what happens to you, but you can control how you react to it. And that’s the very mindset I encourage manufacturing leaders to adopt when addressing human error on the factory floor. By following a few simple lean principles and concepts, you can help your organization prevent mistakes from happening, and change your perception of them when they (inevitably) do.

To Err Is Human

Today’s economic marketplace is characterized by ever-shrinking budgets, increasing operational complexity, and easier access for competitors. Mistakes make it even harder to achieve and maintain success in an already highly competitive environment.

But mistakes are a fact of life. A study conducted by the U.S. military and aerospace programs(1) confirmed that humans are often the least reliable components of complex manufacturing systems. The study showed that even highly trained military personnel make errors about 20 percent of the time in simulated military emergencies. At best, humans cause one error in every 10,000 attempts, or 100 parts per million.

Shigeo Shingo, a leader in the fields of lean manufacturing, operational excellence and continuous process improvement, distinguished between errors and defects. According to Shingo, errors were unavoidable even with good processes and good workers in place.

And with errors come product defects, which Shingo defined as errors that reach the customer. However, unlike errors, he believed defects could be completely eliminated. How? By detecting the errors quickly and acting to prevent them from reaching the customer.

In manufacturing, most errors occur due to:

- Missing process steps

- Process errors

- Mis-set work pieces

- Missing parts

- Wrong parts

- Wrong work pieces

- Faulty machine operation

- Adjustment errors

- Equipment not set up properly

- Tools and jigs inadequately prepared

All of these can lead to product defects that can inadvertently reach customers and impact their experience with your product to varying degrees, from causing minor annoyances or lost trust to much more serious implications like health and safety dangers.

So, if errors are inevitable, how do you prevent them from reaching your customers?

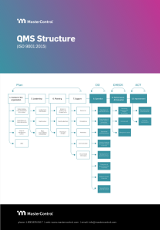

Leaning on the House of Lean

The purpose of lean is to reduce waste and optimize efficiency in a manufacturing environment. Lean thinking is often depicted as a house. Just like a physical house, the House of Lean has a foundation, walls and a roof, each of which is critical to the integrity of the structure and must be present for the system to work. The foundational elements of the House of Lean are:

- Stability – leveling variation caused by things like product model changes, introducing new products and processes, and changes in plant facilities.

- Standardization – developing and applying clear, simple and visual standards for doing work.

- Just in Time – preventing the accumulation of waiting product.

- Involvement – encouraging adoption of lean programs through training and culture.

- Jidoka – automating processes to augment people, resulting in fewer defects and quicker defect containment.

These elements are interdependent and work together to support the “roof,” or ultimate objective, of the House of Lean: ensuring high-quality product is delivered to the customer on time and to spec.

The House of Lean

The House of Lean

A Revolution in Quality Management

With its goal of achieving the highest quality at the lowest cost with the shortest lead time, quality management is hard. It can feel like a constant contradiction – at times seeming like you must give up one important quality element to attain another. It can also feel like one big balancing act between different commitments to customers, whether those commitments are delivery dates, quantity levels, quality levels, or something else. Add the unpredictable nature of mistakes to the already complex equation, and the challenge facing quality management increases exponentially.

That’s where lean comes in. Jidoka is a lean term that describes the symbiotic relationship between intelligent workers and machines to achieve the goal of minimizing the occurrence of defects (High Process Capability), quickly identifying and containing those that do occur (Containment), and embedding a communication system that allows you to take quick countermeasures to prevent them from occurring again or reaching the customer (Feedback).

But for Shingo, simply detecting defects was not enough. He further developed and expanded the concept of Jidoka, introducing the rather revolutionary idea that it is acceptable to go as far as stopping the production line to find the root cause of a defect, shifting the mindset from expecting defects to actively preventing them, and making 100 percent inspections possible at a low cost.

In so doing, Shingo invented Poka-Yoke, or stopping mistakes from becoming defects altogether. Poka-Yoke can be attained by implementing simple and inexpensive failure-proofing devices or actions that can remove or significantly reduce the chance of an error, or make the error so obvious that there is almost no likelihood of it reaching the customer. Common Poka-Yoke devices or actions include checklists, workflow changes, highlighted form fields, software error or reminder messages, and many more. If a mistake or abnormal situation still occurs, human workers are empowered to take necessary action to prevent a defect from moving forward, up to and including halting a process or shutting down line equipment.

Steps for Lean Success

Your company may have already implemented a Statistical Process Control (SPC) program. This type of system reports the quantity of defects that you can realistically expect from a process, which is data that can be highly beneficial to your business. But knowing is only half the battle – it’s what you do with the information that counts. Below are seven ways you can proactively address the potential defects identified by your SPC:

- Recognize the issue and act quickly internally

- Feel empathy for the customer

- Find the root cause and avoid future issues

- Report to all internal/external stakeholders

- Rebuild lost trust caused by previous issues

- Communicate transparently with the supply chain

- Maintain trust through integrity and honesty

In manufacturing, even the smallest mistake can have serious implications that jeopardize the success of your business. But by implementing and practicing these tried-and-true lean principles, inevitable mistakes don’t need to result in defects, and can even lead to efficiencies and process improvements that revolutionize your operations and set you apart from the competition.

Reference

1. System Safety 2000: A Practical Guide for Planning, Managing, and Conducting System Safety Programs. 1991. Van Nostrand Reinhold.